Swinging Atwood's machine

The swinging Atwood's machine (SAM) is a mechanism that resembles a simple Atwood's machine except that one of the masses is allowed to swing in a two-dimensional plane, producing a dynamical system that is chaotic for some system parameters and initial conditions.

Specifically, it comprises two masses (the pendulum, mass  and counterweight, mass

and counterweight, mass  ) connected by a inextensible, massless string suspended on two frictionless pulleys of zero radius such that the pendulum can swing freely around its pulley without colliding with the counterweight.[1]

) connected by a inextensible, massless string suspended on two frictionless pulleys of zero radius such that the pendulum can swing freely around its pulley without colliding with the counterweight.[1]

The conventional Atwood's machine allows only "runaway" solutions (i.e. either the pendulum or counterweight eventually collides with its pulley), except for  . However, the swinging Atwood's machine with

. However, the swinging Atwood's machine with  has a large parameter space of conditions that lead to a variety of motions that can be classified as terminating or non-terminating, periodic, quasiperiodic or chaotic, bounded or unbounded, singular or non-singular[1][2] due to the pendulum's reactive centrifugal force counteracting the counterweight's weight.[1] Research on the SAM started as part of a 1982 senior thesis entitled Smiles and Teardrops (referring to the shape of some trajectories of the system) by Nicholas Tufillaro at Reed College, directed by David J. Griffiths.[3]

has a large parameter space of conditions that lead to a variety of motions that can be classified as terminating or non-terminating, periodic, quasiperiodic or chaotic, bounded or unbounded, singular or non-singular[1][2] due to the pendulum's reactive centrifugal force counteracting the counterweight's weight.[1] Research on the SAM started as part of a 1982 senior thesis entitled Smiles and Teardrops (referring to the shape of some trajectories of the system) by Nicholas Tufillaro at Reed College, directed by David J. Griffiths.[3]

Contents |

Equations of motion

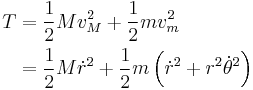

The swinging Atwood's machine is a system with two degrees of freedom. We may derive its equations of motion using either Hamiltonian mechanics or Lagrangian mechanics. Let the swinging mass be  and the non-swinging mass be

and the non-swinging mass be  . The kinetic energy of the system,

. The kinetic energy of the system,  , is:

, is:

where  is the distance of the swinging mass to its pivot, and

is the distance of the swinging mass to its pivot, and  is the angle of the swinging mass relative to pointing straight downwards. The potential energy

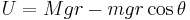

is the angle of the swinging mass relative to pointing straight downwards. The potential energy  is solely due to the acceleration due to gravity:

is solely due to the acceleration due to gravity:

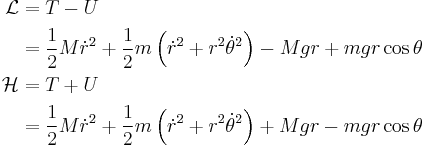

We may then write down the Lagrangian,  , and the Hamiltonian,

, and the Hamiltonian,  of the system:

of the system:

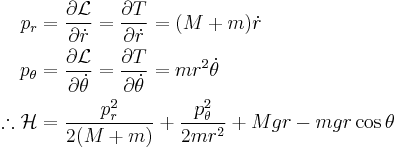

We can then express the Hamiltonian in terms of the canonical momenta,  ,

,  :

:

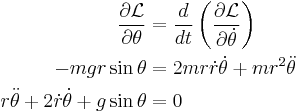

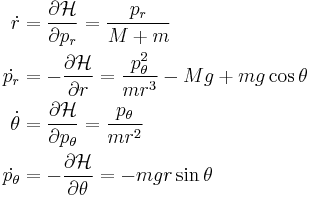

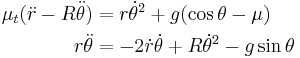

Lagrange analysis can be applied to obtain two second-order coupled ordinary differential equations in  and

and  . First, the

. First, the  equation:

equation:

And the  equation:

equation:

We simplify the equations by defining the mass ratio  . The above then becomes:

. The above then becomes:

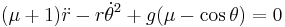

Hamiltonian analysis may also be applied to determine four first order ODEs in terms of  ,

,  and their corresponding canonical momenta

and their corresponding canonical momenta  and

and  :

:

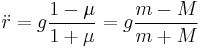

Notice that in both of these derivations, if one sets  and angular velocity

and angular velocity  to zero, the resulting special case is the regular non-swinging Atwood machine:

to zero, the resulting special case is the regular non-swinging Atwood machine:

The swinging Atwood's machine has a four-dimensional phase space defined by  ,

,  and their corresponding canonical momenta

and their corresponding canonical momenta  and

and  . However, due to energy conservation, the phase space is constrained to three dimensions.

. However, due to energy conservation, the phase space is constrained to three dimensions.

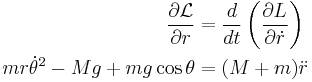

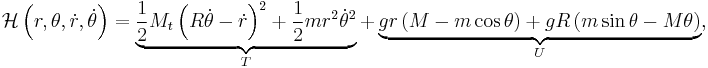

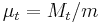

System with massy pulleys

If the pulleys in the system are taken to have moment of inertia  and radius

and radius  , the Hamiltonian of the SAM is then[4]:

, the Hamiltonian of the SAM is then[4]:

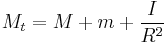

Where Mt is the effective total mass of the system,

This reduces to the version above when  and

and  become zero. The equations of motion are now[4]:

become zero. The equations of motion are now[4]:

where  .

.

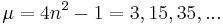

Integrability

Hamiltonian systems can be classified as integrable and nonintegrable. SAM is integrable when the mass ratio  .[5] The system also looks pretty regular for

.[5] The system also looks pretty regular for  , but the

, but the  case is the only integrable mass ratio found so far. For many other values of the mass ratio (and initial conditions) SAM displays chaotic motion.

case is the only integrable mass ratio found so far. For many other values of the mass ratio (and initial conditions) SAM displays chaotic motion.

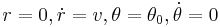

Numerical studies indicate that when the orbit is singular (initial conditions:  ), the pendulum executes a single symmetrical loop and returns to the origin, regardless of the value of

), the pendulum executes a single symmetrical loop and returns to the origin, regardless of the value of  . When

. When  is small (near vertical), the trajectory describes a "teardrop", when it is large, it describes a "heart". These trajectories can be exactly solved algebraically, which is unusual for a system with a non-linear Hamiltonian.[6]

is small (near vertical), the trajectory describes a "teardrop", when it is large, it describes a "heart". These trajectories can be exactly solved algebraically, which is unusual for a system with a non-linear Hamiltonian.[6]

Trajectories

The swinging mass of the swinging Atwood's machine undergoes interesting trajectories or orbits when subject to different initial conditions, and for different mass ratios. These include periodic orbits and collision orbits.

Periodic orbits

For certain conditions, system exhibits complex harmonic motion. A consequence is that when the different harmonic components are in phase, the resulting trajectory is simple and periodic, such as the "smile" trajectory, which resembles that of an ordinary pendulum, and various loops.[3][7] In general a periodic orbit exists when the following is satisfied[1]:

The following are plots of arbitrarily selected periodic orbits.

| Selection of periodic orbits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Singular orbits

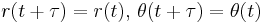

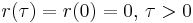

The motion is singular if at some point, the swinging mass passes through the origin. Since the system is invariant under time reversal and translation, it is equivalent to say that the pendulum starts at the origin and is fired outwards:[1]

The region close to the pivot is singular, since  is close to zero and the equations of motion require dividing by

is close to zero and the equations of motion require dividing by  . As such, special techniques must be used to rigorously analyze these cases.[8]

. As such, special techniques must be used to rigorously analyze these cases.[8]

The following are plots of arbitrarily selected singular orbits.

| Selection of singular orbits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Collision orbits

Collision (or terminating singular) orbits are subset of singular orbits formed when the swinging mass is ejected from the its pivot with an initial velocity, such that it returns back to the pivot (i.e. it collides with the pivot):

Under these conditions, the counterweight mass,  must instantaneously change direction, causing an infinite tension in the connecting string. Thus we may consider the motion to terminate at this time.[1]

must instantaneously change direction, causing an infinite tension in the connecting string. Thus we may consider the motion to terminate at this time.[1]

Some such trajectories are "hearts", "rabbit ears" and "teardrops", described in Tufillaro's initial paper as well as later ones.[3][6][7][8]

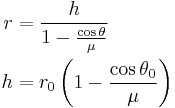

Boundedness

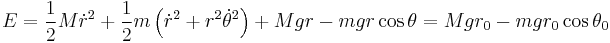

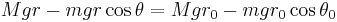

For any initial position, it can be shown that the swinging mass is bounded by a curve that is a conic section.[2] The pivot is always a focus of this bounding curve. The equation for this curve can be derived by analyzing the energy of the system, and using conservation of energy. Let us suppose that  is released from rest at

is released from rest at  and

and  . The total energy of the system is therefore:

. The total energy of the system is therefore:

However, notice that in the boundary case, the velocity of the swinging mass is zero.[2] Hence we have:

To see that it is the equation of a conic section, we isolate for  :

:

Note that the numerator is a constant dependent only on the initial position in this case, as we have assumed the initial condition to be at rest. However, the energy constant  can also be calculated for nonzero initial velocity, and the equation still holds in all cases.[2] The eccentricity of the conic section is

can also be calculated for nonzero initial velocity, and the equation still holds in all cases.[2] The eccentricity of the conic section is  . For

. For  , this is an ellipse, and the system is bounded and the swinging mass always stays within the ellipse. For

, this is an ellipse, and the system is bounded and the swinging mass always stays within the ellipse. For  , it is a parabola and for

, it is a parabola and for  it is a hyperbola; in either of these cases, it is not bounded. As

it is a hyperbola; in either of these cases, it is not bounded. As  gets arbitrarily large, the bounding curve approaches a circle. The region enclosed by the curve is known as the Hill's region.[2]

gets arbitrarily large, the bounding curve approaches a circle. The region enclosed by the curve is known as the Hill's region.[2]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Tufillaro, Nicholas B.; Abbott, Tyler A.; Griffiths, David J. (1984). "Swinging Atwood's Machine". American Journal of Physics 52 (10): 895–903. Bibcode 1984AmJPh..52..895T. doi:10.1119/1.13791.

- ^ a b c d e Tufillaro, Nicholas B.; Nunes, A.; Casasayas, J. (1988). "Unbounded orbits of a swinging Atwood's machine". American Journal of Physics 56: 1117. Bibcode 1988AmJPh..56.1117T. doi:10.1119/1.15774.

- ^ a b c Tufillaro, Nicholas B. (1982). Smiles and Teardrops (Thesis). Reed College.

- ^ a b Pujol, Olivier; Perez, J.P.; Simo, C.; Simon, S.; Weil, J.A. (2010). "Swinging Atwood's Machine: Experimental and numerical results, and a theoretical study". Physica D 239 (12): 1067–1081. Bibcode 2010PhyD..239.1067P. doi:10.1016/j.physd.2010.02.017.

- ^ Tufillaro, Nicholas B. (1986). "Integrable motion of a swinging Atwood's machine". American Journal of Physics 54 (2): 142. Bibcode 1986AmJPh..54..142T. doi:10.1119/1.14710.

- ^ a b Tufillaro, Nicholas B. (1994). "Teardrop and heart orbits of a swinging Atwoods machine,". The American Journal of Physics 62 (3): 231–233. Bibcode 1994AmJPh..62..231T. doi:10.1119/1.17602.

- ^ a b Tufillaro, Nicholas B. (1985). "Motions of a swinging Atwood's machine". Journal de Physique 46 (9): 1495–1500. doi:10.1051/jphys:019850046090149500.

- ^ a b Tufillaro, Nicholas B. (1985). "Collision orbits of a swinging Atwood's machine". Journal de Physique 46: 2053–2056. doi:10.1051/jphys:0198500460120205300.

Further reading

- Almeida, M.A., Moreira, I.C. and Santos, F.C. (1998) "On the Ziglin-Yoshida analysis for some classes of homogeneous hamiltonian systems", Brazilian Journal of Physics Vol.28 n.4 São Paulo Dec.

- Barrera, Jan Emmanuel (2003) Dynamics of a Double-Swinging Atwood's machine, B.S. Thesis, National Institute of Physics, University of the Philippines.

- Babelon, O, M. Talon, MC Peyranere (2010), "Kowalevski's analysis of a swinging Atwood's machine," Journal of Physics A-Mathematical and Theoretical Vol. 43 (8).

- Bruhn, B. (1987) "Chaos and order in weakly coupled systems of nonlinear oscillators," Physica Scripta Vol.35(1).

- Casasayas, J., N. B. Tufillaro, and A. Nunes (1989) "Infinity manifold of a swinging Atwood's machine," European Journal of Physics Vol.10(10), p173.

- Casasayas, J, A. Nunes, and N. B. Tufillaro (1990) "Swinging Atwood's machine: integrability and dynamics," Journal de Physique Vol.51, p1693.

- Chowdhury, A. Roy and M. Debnath (1988) "Swinging Atwood Machine. Far- and near-resonance region", International Journal of Theoretical Physics, Vol. 27(11), p1405-1410.

- Griffiths D. J. and T. A. Abbott (1992) "Comment on ""A surprising mechanics demonstration,"" American Journal of Physics Vol.60(10), p951-953.

- Moreira, I.C. and M.A. Almeida (1991) "Noether symmetries and the Swinging Atwood Machine", Journal of Physics II France 1, p711-715.

- Nunes, A., J. Casasayas, and N. B. Tufillaro (1995) "Periodic orbits of the integrable swinging Atwood's machine," American Journal of Physics Vol.63(2), p121-126.

- Ouazzani-T.H., A. and Ouzzani-Jamil, M., (1995) "Bifurcations of Liouville tori of an integrable case of swinging Atwood's machine," Il Nuovo Cimento B Vol. 110 (9).

- Olivier, Pujol, JP Perez, JP Ramis, C. Simo, S. Simon, JA Weil (2010), "Swinging Atwood's Machine: Experimental and numerical results, and a theoretical study," Physica D 239, pp. 1067–1081.

- Sears, R. (1995) "Comment on "A surprising mechanics demonstration," American Journal of Physics, Vol. 63(9), p854-855.

- Yehia, H.M., (2006) "On the integrability of the motion of a heavy particle on a tilted cone and the swinging Atwood machine", Mechanics Research Communications Vol. 33 (5), p711–716.

External links

- Example of use in undergraduate research: symplectic integrators

- Imperial College Course

- Oscilaciones en la máquina de Atwood

- "Smiles and Teardrops" (1982)

- 2007 Workshop

- 2010 Videos of a experimental Swinging Atwood's Machine

- Update on a Swinging Atwood's Machine at 2010 APS Meeting, 8:24 AM, Friday 19 March 2010, Portland, OR

- Interactive web application of the Swinging Atwood's Machine

|

||||||||||||||